Laeeq Babree. Letter from Laeeq Babree. To N. M. Rashed. Feb. 28, 1970. 2 pp. 1 sheet. 8 x 10". Blue ballpoint pen on white paper. Letter from Laeeq Babree to N. M. Rashed. Letterhead: "Dr. Laeeq Babree, Department of French, Government College, Lahore". On top of first page the date 6/3/71 is written. Urdu. Box 2. Folder 3: Correspondence. 012. Digitized by Zain Mian. Catalogued by Yasmin Rashed Hassan. Donated (2015) by Yasmin Rashed Hassan to the Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University, Montreal. Full text here.

The modernist Punjabi poet Laeeq Ahmad Babree (1931-2003) is one of the most interesting lesser-known figures represented in the Archive. Babree was well-acquainted with the works of French modernists, and particularly with Baudelaire, whose Spleen de Paris he had translated by 1982 (as Paris kā karb). Babree had completed his Doctorate in French Literature at the University of Paris in 1968. After returning to Lahore, he became a professor of French at Punjab University. His correspondence with Rashed as preserved in the Archive begins in 1969.

This letter to Rashed, written on February 28, 1971, appears to have been received by Rashed on March 6, 1971. In it Babree mentions the appointment of the psychologist Makhdum Muhammad Ajmal (1919-1994) as principal of Government College, and Ajmal's willingness to invite Rashed and Faiz Ahmad Faiz to an event at G. C. in March. He is in contact with Munir Niazi, who had published Rashed's Lā=Insān in 1969; as well as with Rashed's correspondent the Urdu poet Qayyum Nazar, who was the first professor of Punjabi at Punjab University. Rashed's and Babree's shared love of French modernism made for a warm correspondence, and Babree was able to use his academic position to give the admired modernist pioneer a forum to speak at Government College, which was then in its heyday.

An abstract of the letter:

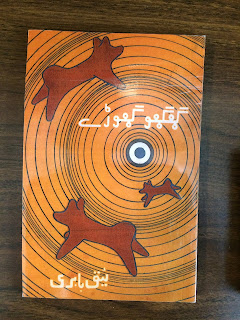

Babree writes that the title of this collection, "Clay Horses," involved a hidden satire. A blurb pasted into the book suggests to us that the short symbolist poems it contained are each like small playthings. The symbol of the ghugghū ghoṛā or clay horse plays with the relation between silence, noise, and speech. "Ghugghū" alone means a hollow clay toy which makes a noise when blown into. But when referring to a person "ghugghū" indicates they are dumb or stupid. Thirdly there is the ghugghū ghoṛā, a mute, knobbly plaything of clay. A blurb pasted into Babree's book suggests the relationship between the title and the book: The short symbolist poems are the clay horses themselves. "Ghugghū ghoṛā" is therefore a description of Babree's poetry. How so? Supposedly poetry tries to communicate something to its audience. But Babree's poetry, in keeping with symbolist precepts, presents the reader with its mute texture and its sound, attempting to withhold the kernel of Meaning. Babree knew the symbolist movement well. Apart from his thorough familiarity with Baudelaire, another evidence of this is his participation in the Société de Symbolisme's May 1966 conference in Paris on "Symbolism and Language."

We thank Babree's wife, Khalida L. Babree, for her kindness in providing us with a copy of Ghugghū ghoṛe, which has been deposited in the Islamic Studies Library at McGill, along with other materials to aid our research on Laeeq Babree, his literary work and his relation to Rashed.

The modernist Punjabi poet Laeeq Ahmad Babree (1931-2003) is one of the most interesting lesser-known figures represented in the Archive. Babree was well-acquainted with the works of French modernists, and particularly with Baudelaire, whose Spleen de Paris he had translated by 1982 (as Paris kā karb). Babree had completed his Doctorate in French Literature at the University of Paris in 1968. After returning to Lahore, he became a professor of French at Punjab University. His correspondence with Rashed as preserved in the Archive begins in 1969.

This letter to Rashed, written on February 28, 1971, appears to have been received by Rashed on March 6, 1971. In it Babree mentions the appointment of the psychologist Makhdum Muhammad Ajmal (1919-1994) as principal of Government College, and Ajmal's willingness to invite Rashed and Faiz Ahmad Faiz to an event at G. C. in March. He is in contact with Munir Niazi, who had published Rashed's Lā=Insān in 1969; as well as with Rashed's correspondent the Urdu poet Qayyum Nazar, who was the first professor of Punjabi at Punjab University. Rashed's and Babree's shared love of French modernism made for a warm correspondence, and Babree was able to use his academic position to give the admired modernist pioneer a forum to speak at Government College, which was then in its heyday.

An abstract of the letter:

Babree has received the programme of Rashed's upcoming trip to Pakistan. The principal at Government College is Muhammad Ajmal, formerly head of the Psychology Department, for whom Babree has words of praise. Babree has suggested to Ajmal that when Rashed comes in March they should invite him to Government College. Ajmal immediately agreed, and suggested that he should be invited for March 25th. Dinner would be given by Government College and Faiz Ahmed Faiz would also be invited. Ajmal must leave Lahore for a science conference around the 28th or 29th of March.

Babree meets with Munir Niazi regularly. Two or three days ago there was a Punjabi majlis chaired by Munir Niazi. Babree believes that Punjabi is slowly being recognized as a language of the shurafā. Seven or eight years ago when he wrote his first Punjabi poetry, he was mocked. Now Punjabi has been established as a subject at Punjab University, with Qayyum Nazar teaching. Beginning tomorrow, Punjabi news will be broadcast over the Lahore-Rawalpindi-Multan national hookup radio.

When Babree had sent Rashed his Punjabi poem "Pinghoṛe", Rashed had asked him about the word "tuhoṛ," which Babree will explain when they meet. He is sending a copy of his Punjabi poem "Gāhaṛ." His Punjabi collection Ghugghū ghoṛe is about to be printed (1971). There is an inside joke in the title. Qayyum Nazar has also received Rashed's letter. He no longer works for Pakistan Council; he now works for the Textbook Board.The collection of Punjabi poetry to which Babree refers, Ghugghū ghoṛe (Clay Horses), would be published a few months later on June 10, 1971 by the Majlis Shah Husain in Lahore. This book, which is rare in the West (the only holding appearing in Worldcat is in the British Library), had a print run of 500 copies and sold for Rs. 300.

Babree writes that the title of this collection, "Clay Horses," involved a hidden satire. A blurb pasted into the book suggests to us that the short symbolist poems it contained are each like small playthings. The symbol of the ghugghū ghoṛā or clay horse plays with the relation between silence, noise, and speech. "Ghugghū" alone means a hollow clay toy which makes a noise when blown into. But when referring to a person "ghugghū" indicates they are dumb or stupid. Thirdly there is the ghugghū ghoṛā, a mute, knobbly plaything of clay. A blurb pasted into Babree's book suggests the relationship between the title and the book: The short symbolist poems are the clay horses themselves. "Ghugghū ghoṛā" is therefore a description of Babree's poetry. How so? Supposedly poetry tries to communicate something to its audience. But Babree's poetry, in keeping with symbolist precepts, presents the reader with its mute texture and its sound, attempting to withhold the kernel of Meaning. Babree knew the symbolist movement well. Apart from his thorough familiarity with Baudelaire, another evidence of this is his participation in the Société de Symbolisme's May 1966 conference in Paris on "Symbolism and Language."

We thank Babree's wife, Khalida L. Babree, for her kindness in providing us with a copy of Ghugghū ghoṛe, which has been deposited in the Islamic Studies Library at McGill, along with other materials to aid our research on Laeeq Babree, his literary work and his relation to Rashed.

Keywords: #Laeeq_Ahmad_Babree, #Khalida_Laeeq_Babree, #Charles_Baudelaire, #Qayyum_Nazar, #Makhdum_Muhammad_Ajmal, #Faiz_Ahmad_Faiz, #Punjabi_language_&_literature, #Punjab_University, #Government_College_Lahore, #Université_de_Paris, #Sorbonne, #Paris, #French_language_&_literature, #Ghuggu_ghore, #Pinghore, #Gahlar, #Majlis_Shah_Husain, #Société_de_Symbolisme, #radio, #modernism, #symbolism, #silence, #letter, #handwritten, #Lahore